BLOG TOUR: As Far As I Can Tell by Philip Gambone (Excerpt + Q & A with Author)

BLOG TOUR

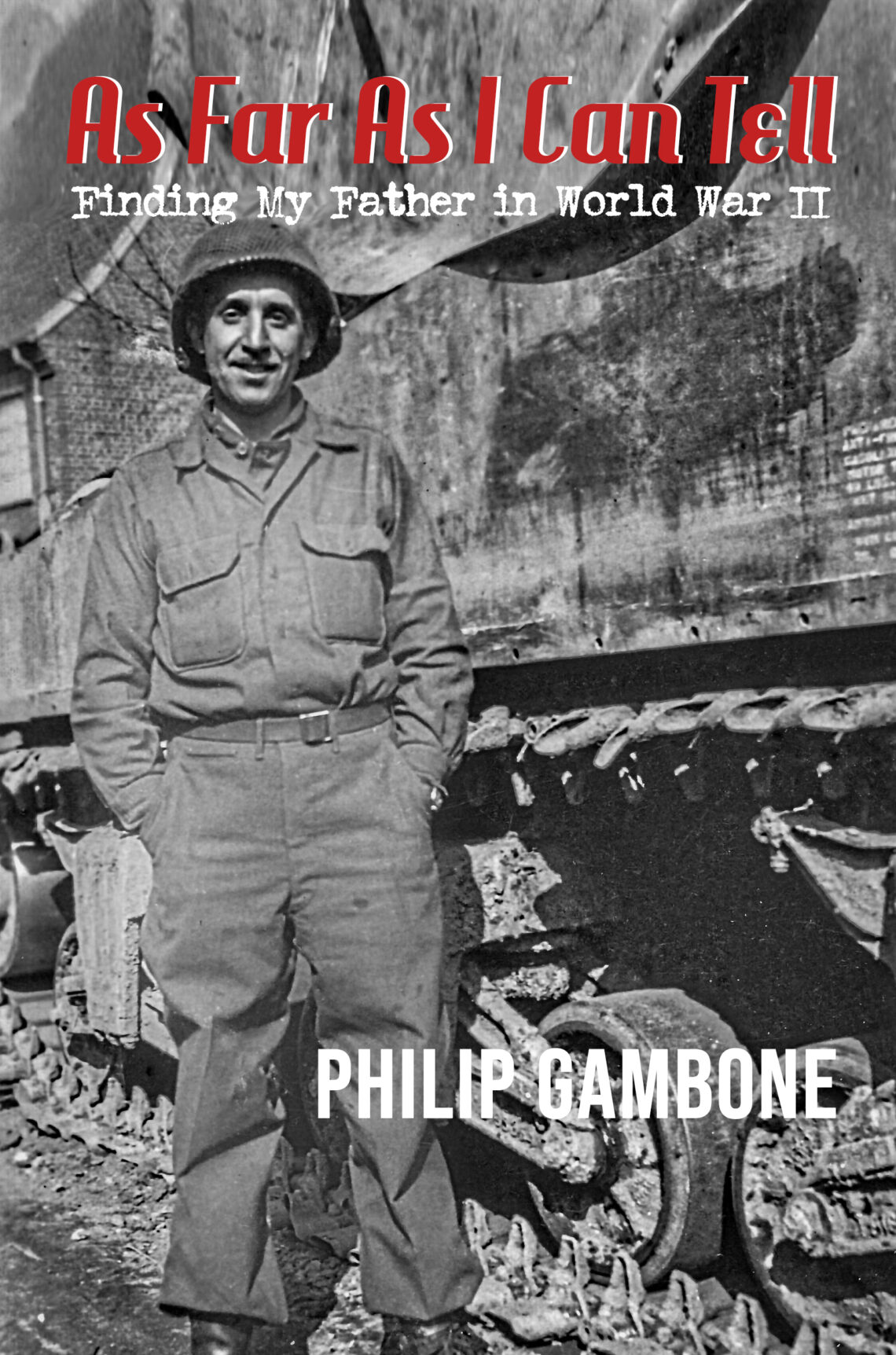

Book Title: As Far As I Can Tell: Finding My Father In World War II

Author: Philip Gambone

Publisher: Rattling Good Yarns Press

Release Date: October 30, 2020

Genre: Memoir

Trope/s: Father/Son Relationships

Themes: Connecting to the past, Understanding our fathers,

Father/Son silence and the inherent lack of communications,

Coming to terms with history

Heat Rating: 2 flames

Length: 155 000 words/474 pages

It is a standalone book.

Buy Links

(Note – The Rattling Good Yarns online store only ships within the US)

2021 Lambda Literary Award Nominated

Blurb

Philip Gambone, a gay man, never told his father the reason why he was rejected from the draft during the Vietnam War. In turn, his father never talked about his participation in World War II. Father and son were enigmas to each other. Gambone, an award-winning novelist and non-fiction writer, spent seven years uncovering who the man his quiet, taciturn father had been, by retracing his father’s journey through WWII. As Far As I Can Tell not only reconstructs what Gambone’s father endured, it also chronicles his own emotional odyssey as he followed his father’s route from Liverpool to the Elbe River. A journey that challenged the author’s thinking about war, about European history, and about “civilization.”

“Philip Gambone weaves a moving memoir of his family, a vivid portrayal of his travels through the locales of WWII, and a powerful description of what that war was like to the men who fought it on the ground into a seamless and eloquent narrative.” — Hon. Barney Frank, former Congressman, Massachusetts

“A single question pulses through As Far As I Can Tell: why didn’t my father talk about his time in the war? With meticulous research, Philip Gambone puts sound to silence, offering us a book-length love letter, not just to his father, but to anyone whose life has been hemmed in by obligation, obedience, and the brutality of the system. It’s also a coming to terms with the unknown in others, which is its own hard grace. A vital, dynamic read.” — Paul Lisicky, author of Later: My Life at the Edge of the World

“As Far As I Can Tell is a fascinating mix of autobiography, travelogue, and historical research that not only takes us on a great adventure in search of what World War Two was like for those who fought in the European theater but probes that most difficult of all subjects, the relationship between a father and a son — in this case, a gay son. Extensively researched, highly literate and profoundly thoughtful, the story Gambone tells uses not only soldiers’ memoirs but writers as disparate as Samuel Johnson and James Lord to make this a reader’s delight.”— Andrew Holleran, author of Dancer from the Dance

Excerpt

On February 12, 1942, Dad reported for induction. The chief business was the physical examination, which was conducted assembly-line fashion. The inductees were naked, wearing only a number around their necks. It was the most comprehensive physical most of them had ever had. For some it was intimidating, for others embarrassing.

Most inductees were eager to pass the physical exam, so eager in fact that in many cases, they indulged in “negative malingering,” trying to conceal conditions that might get them disqualified. Once the physical was out of the way, the only screening that remained was a brief interview with an army psychiatrist, who had been instructed to look for “neuropsychosis,” a diagnosis that covered all sort of emotional ills from phobias to excessive sweating and evidence of mental deficiency.

Paul Marshall, who ended up in the same division as Dad, remembered being asked at his physical if he liked girls. “I didn’t quite understand what he meant about it. I told him, ‘Why sure, I like girls.’” Later Marshall figured out what he was really being asked. “The ultimate question mark of manliness,” James Lord, himself a homosexual, recalled. “Do you like girls? Or prefer confinement in a federal penitentiary for the remainder of your unnatural life.” The terror of being considered a sexual leper or worse, “unfit to honor the flag of your forebears,” was real. Lord answered, Yes, he liked girls, and was promptly accepted into the army.

Not every homosexual inductee lied. Some, like Donald Vining, came clean with his interviewer, who turned out to be “marvelously tolerant, taking the whole thing easily and calmly, without shock and without condescension.” The interviewer marked Vining’s papers “sui generis ‘H’ overt,” and he was out.

My father passed his induction physical. Hale, hearty, and decidedly heterosexual, he needed none of the remedial medical work—dental, optometric—that millions of other inductees did. With the physical and the psychological screenings done, Dad signed his induction papers, was fingerprinted, and issued a serial number. The final piece of business was the administration of the oath of allegiance, done, according to army regulations, “with proper ceremony.” Once sworn in, Dad was sent home to put things in order before he went off to Camp Perry to be processed for basic training.

Twenty-eight years after Dad’s, my own induction notice arrived, during my senior year in college. I was instructed to report to my hometown on May 6, where the Army would put me on a bus and drive me to the Armed Forces Examining and Entrance Station in South Boston. I remember standing, before dawn, on a curb outside the town offices waiting for the bus. Other fellows from my high school were there, and I nervously tried to make small talk with them. We’d had nothing in common in high school, and the situation hadn’t changed in the intervening years.

My recollection of that day is shrouded in numbness. I remember standing in a line, stripped to my underwear, making my way from one examining station to the next. I kept assuring myself I could not possibly go to Vietnam, that the good fortune I’d enjoyed so far would see me to a different destiny than the one where I would end up dead in a jungle in Southeast Asia.

I was clutching a letter from my dentist attesting to the fact that I needed braces, in those days a cause for rejection. But aside from that, I had not taken any steps to ensure that I wouldn’t be taken. I’d heard stories of guys planning to go to their induction physicals drunk, or stoned, or wearing dresses and makeup. Others said they would flee to Canada or apply for conscientious objector status. I had made no such plans. Throughout senior year, I had been sitting on my damn butt, still banking on magic or luck to get me the hell out.

I passed every exam. I was not overweight. I did not have flat feet or a heart murmur. My blood pressure was excellent. At one station, I handed over the dentist’s letter. The examiner gave it a perfunctory glance and tucked it into my file.

At last, I came to the psychological screening area. All I remember is the examiner asking me if I’d ever had any homosexual experiences. And when I said yes, he followed up with a few more questions. Had I sought counseling? Did I intend to stop? That was it. He thanked me and I moved on. Less than two weeks later, I received a notice from the AFEES: “Found Not Acceptable

for Induction Under Current Standards.” I’d been declared 4-F. In the parlance of the day, I had “fagged out.” My parents thought the dentist’s letter about braces had done the trick.

Q & A With Philip Gambone

The prized possession you value above all others…

I don’t consider myself a possessive person, but my collection of books is probably the one I value most. I live in a small apartment, so they take up a lot of room. Right now, I’m actually trying to divest myself of many of my books—selling them, giving them away—but it’s tough. I guess I’m more possessive than I thought.

The unqualified regret you wish you could amend…

When I was 21, I was asked to be Leonard Bernstein’s houseboy for the summer. I turned it down. The thought of what that might have led to continues to intrigue me.

The book that holds everlasting resonance…

Homer’s Odyssey. I’ve read it (and taught it) almost 20 times, and every time I find something new—in terms of use of language, structure, ideas, values, and the sheer delight of a great story marvelously told. My own book, As Far As I Can Tell: Finding My Father in World War II, is an odyssey tale—the story of a modern Telemachus in search of information about his warrior father.

The film you can watch time and time again…

David Lean’s 1946 Great Expectations. It’s not perfect and the last five minutes nearly ruin a great film and a superb novel, but the rest is a masterful reduction of a complex masterpiece that gets to the heart of Dickens’ classic. Lean’s use of atmosphere is astonishing. The acting—all around—is superb. Already you can see his great directing skills at play. I know every scene practically by heart, and they are always mesmerizing.

The person who influenced you the most…

Well, the obvious answer, I guess, is my parents. But I’ve had certain teachers who also instilled in me values that have stuck with me: the band leader in high school who taught me about hard work and discipline; the graduate student teacher in college who made me feel I had something worth saying; and of course certain authors whose excellence I’ve tried to emulate.

The unlikely interest that engages your curiosity…

How about this: I’m crazy about Italian baroque opera, 18th-century British portraiture, and Zen Buddhism.

The poem that touches your soul…

I started off my writing career as a poet and won some accolades and prizes in college. I am constantly reading poetry—classic and contemporary. For sheer exquisite use of the English language: Keats and Shakespeare. For reminding me of what is best about the American soul: Walt Whitman. For the joie de vivre of gay urban life: Frank O’Hara. Other favorite gay poets: Cavafy and Mark Doty. For the beauty and mysterious serenity of nature: anything by Tang dynasty Chinese poets. Right now, the poem that most touches my soul—I come back to it again and again—“Wait” by Galway Kinnell.

The event that altered the course of your life…

When I was 16, my parents sent me off to a fancy New England prep school for the summer. That’s when I first fell in love with literature in a serious way.

The song that means the most to you…

I’m not much of a pop music fan. But “That’s the Way Life Is” by the Pet Shop Boys never ceases to bring me to tears of joy. As for classical music: any song by Schubert!

The happiest moment you will cherish forever…

I have many! I’m basically a happy person. I try to live with gratitude every day. But, for a writer, the happiest moment was when my first short story was accepted for publication. The editor of the journal initially rejected it, then wrote back to say that the story was haunting him and could he have another look. A few weeks later, it was accepted. That was over 30 years ago. It gave me the confidence to keep going.

Your early recollections of writing fiction…

Turgid, long-winded, far too influenced by Henry James! It was only after I started reading contemporary American short stories, especially John Updike’s, that I began to develop a voice that was true.

The way you would spend your fantasy twenty-four hours, with no travel restrictions…

When I travel—and I love to travel!—I try to spend several days in one place. But, if given only twenty-four hours, then I think it would be the temples at Angkor Wat in Cambodia.

The figure from history you would most like to buy a pie and a pint…

The Tang dynasty poet Li Po. My guess is that he’d drink me under the table and still be more lucid, profound, and witty than I could ever hope to be.

The piece of wisdom you would pass onto a child…

Ha! I’m not sure children listen to wisdom (I didn’t when I was a child). So I’d go easy on trying to pass wisdom on to them. The best things you can give a child is a sense of their own worth, their own goodness, their ability to have success. I’d share with them my delight in the world—the natural world and the built world. I’d share with them the notion that boredom is a function of lack of attention.

The treasured item you lost and wish you could have again…

My father’s field binoculars from World War II.

The philosophy that underpins your life…

As an aspiring Buddhist (is there any other kind?), I try to live a life of integrity, mindfulness, gratitude, friendliness, and kindness. The three great ways of ancient China—Confucianism, Taoism, and Buddhism—speak to me far more profoundly than much of Western religion and philosophy. I hope a little of that comes through in my book.

The character you enjoyed writing the most…

My father.

The character you found difficult to write…

My father.

The book you enjoyed planning/writing the most…

Each one of my five books (seven if you count the two that were never published) has been one that I’ve enjoyed working on. This latest book took me the longest (almost 8 years) and was, in some ways, the most enjoyable because it drew on new skills—especially research skills—that kept me stimulated.

And the promo…

The book cover features a photo of my father in front of his tank in Germany late in the war (March or April, 1945). People have commented that he looks like me. What I see in that photo is a 29-year-old soldier who has been completely worn down by combat and the horrors he witnessed in his march across Europe. I think it’s a powerful image for the cover.

As Far As I Can Tell is a quest biography about the several-thousand-mile journey I made—both in the field and through extensive research—to track down my father’s wartime experience and to understand my relationship to him and to war in general.

My father, a tank gunner with the Fifth Armored Division, was a citizen-soldier during World War II. Born and raised in Canton, Ohio, he was drafted in 1942 and spent two years in U.S. training camps before shipping overseas. The Fifth Armored Division (the “Victory Division”) fought its way across Normandy, liberated the Duchy of Luxembourg, and then engaged the Germans at the Siegfried Line and in the horrific Battle of the Bulge. They were the first American division to enter Germany and the one closest to Berlin at the end of the War. Many of my father’s buddies did not survive; he did, and he lived the rest of his life with that sad, haunting knowledge.

My father never spoke about his war experience. He wrapped that story in a tight cocoon of silence. In truth, my father and I rarely spoke about anything. From early on in my life as gay man, I learned to wrap myself in a cocoon of my own, choosing to lock my father out of my emerging life. While he and I were not estranged, we conducted a polite, hesitant do-si-do around each other’s silence. Did he know I was gay? Perhaps. Did I fathom the depth of the trauma he had suffered in the War? Not at all.

After he died, I discovered among his effects a scrapbook of photos he had taken during the war, a handful of letters he had written home, and a few other documents related to his wartime experience. This memorabilia—so flimsy and incomplete—stood out to me both as an indictment that I had paid so little attention to my father and what he’d done, and as an invitation to uncover just what sort of man he had been, during the war and after.

In uncovering his story, I aimed to avoid both sentimentality and the congenial, if inconsequential, smallness of “family history.” My quest was about more than that. I wanted to assess the war’s emotional resonance: on him, on his fellow soldiers, and on me. I found myself, like the Russian historian Svetlana Alexievich, becoming “a historian of the soul”—my father’s soul, his generation’s, and mine.

The book interweaves several stories. Based on my research (including dozens of interviews with surviving members of the 5AD), As Far As I Can Tell reconstructs what my father and the men of the Fifth Armored Division endured; it also chronicles my own emotional odyssey as I followed his route from Liverpool to the Elbe River, a journey that challenged my thinking about war, about European history, and about “civilization.” What I discovered—about this man I hardly knew, and about myself, a man who was deemed “unfit” for military service in Vietnam—is the substance of the book.

About the Author

Philip Gambone is a writer of fiction and nonfiction. His debut collection of short stories, The Language We Use Up Here, was nominated for a Lambda Literary Award. His novel, Beijing, was nominated for two awards, including a PEN/Bingham Award for Best First Novel.

Phil has extensive publishing credits in nonfiction as well. He has contributed numerous essays, reviews, features pieces, and scholarly articles to several local and national journals including The New York Times Book Review and The Boston Globe. He is a regular contributor to The Gay & Lesbian Review.

His longer essays have appeared in a number of anthologies, including Hometowns, Sister and Brother, Wrestling with the Angel, Inside Out, Boys Like Us, Wonderlands, and Big Trips.

Phil’s book of interviews, Something Inside: Conversations with Gay Fiction Writers, was named one of the “Best Books of 1999” by Pride magazine. His Travels in a Gay Nation: Portraits of LGBTQ Americans was nominated for an American Library Association Award.

Phil’s scholarly writing includes biographical entries on Frank Kameny in the Dictionary of National Biography (Oxford) and Gary Glickman in Contemporary Gay American Novelists: A Bio-Bibliographical Critical Sourcebook. He also wrote three chapters on Chinese history for two high school textbooks published by Cheng and Tsui.

He is a recipient of artist’s fellowships from the MacDowell Colony, the Helene Wurlitzer Foundation, and the Massachusetts Arts Council. He has also been listed in Best American Short Stories.

Phil taught high school English for over forty years. He also taught writing at the University of Massachusetts, Boston College, and in the freshman expository writing program at Harvard. He was twice awarded Distinguished Teaching Citations by Harvard. In 2013, he was honored by the Department of Continuing Education upon completing his twenty-fifth year of teaching for the Harvard Extension School.

Author Links

Blog/Website | Facebook | Newsletter Sign-up

Follow the tour and check out the other blog posts and interviews here